New study tracks the evolution of stone toolsOver 2.6 million years, humans got more efficient at making stone tools.

Ars Technia

Kiona N. Smith - 3/6/2018, 7:15 AM

Enlarge / Some of the Middle Stone Age stone tools from Jebel Irhoud. Pointed forms such as a-i are common in this period. Also characteristic are the so-called Levellois prepared core flakes. Mohammed Kamal

Enlarge / Some of the Middle Stone Age stone tools from Jebel Irhoud. Pointed forms such as a-i are common in this period. Also characteristic are the so-called Levellois prepared core flakes. Mohammed KamalFor at least 2.6 million years, humans and our ancestors have been making stone tools by chipping off flakes of material to produce sharp edges. We think of stone tools as very rudimentary technology, but producing a usable tool without wasting a lot of stone takes skill and knowledge. That's why archaeologists tend to use the complexity of stone tools as a way to measure the cognitive skills of early humans and the complexity of their cultures and social interactions.

But because the same tool-making techniques didn’t show up everywhere early humans lived, it’s hard to really compare how stone tool technology developed across the whole 2.6 million-year history of stone tool-making or across the broad geographic spread of early humans. To do that, you’ve got to find a common factor.

So a team led by anthropologist Željko Režek of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology decided to study whether the length of the sharp, working edge of stone flakes changed over time relative to the size of the flakes. A longer, sharp edge is more efficient and takes more control and skill to create, so Režek and his colleagues reasoned that it would be a good proxy for how well early humans understood the process of working stone and how well they shared that knowledge with each other.

A quick lesson in stone knapping

When you’re trying to knock a sharp flake off a chunk of stone, the size of the flake and the length of its edge depend on how and where you strike the stone core.

“Stone artifacts vary greatly in complexity, but the physics of stone knapping mean that the most fundamental part of the process of their creation—flake detachment—is similar whether one is producing a single large sharp flake to help butcher an animal or putting the finishing touches to a microlithic weapon component,” wrote University of Bordeaux archaeologist Natasha Reynolds in a comment on Režek’s study.

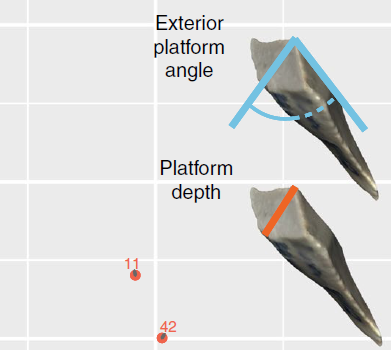

One of the most important factors is the thickness of the flake at the spot where it starts (called the platform depth). Another is the angle between the surface being hit to create the flake and the surface of the stone core that the flake breaks off from (called the exterior platform angle). A larger exterior platform angle will create a flake with a long edge relative to its size. But getting it right takes planning, skill, and knowledge.

Diagram of exterior platform angle and platform depth. Željko Režek

Diagram of exterior platform angle and platform depth. Željko Režek“Controlling these two variables when making a flake requires an ability to direct force at a precise location for a given platform angle,” wrote Režek and his team. “This is a skill that is uniquely human.” And that, they say, means that the length of a flake’s working edge can reveal something about the skill of its makers. That, in turn, can offer clues about how hominin cultures advanced and passed along new skills over the last 2.5 million years.

So Režek and his colleagues measured the edges of more than 19,000 stone flakes from 81 groups of artifacts from sites in Africa, southwest Asia, and Western Europe, spanning a stretch of human history from Homo habilis 2.6 million years ago to modern humans 12,000 years ago. Those sites contain artifacts from at least five hominin species: H. habilis, H. erectus, H. heidelbergensis, Neanderthals, and modern humans.

Edges get longer, but also more diverse

Throughout the Pleistocene, the average length of working edges increased relative to flake size. Early Pleistocene stone flakes, made by H. habilis and H. erectus before about 1 million years ago, had the shortest working edges in the study. After about 1 million years ago, though, flake edges started getting longer, and it appears that H. erectus, followed by H. heidelbergensis and Neanderthals, learned how to control platform depth and exterior platform angle in order to get more sharp edges relative to the size of their flakes.

That trend continued with modern humans, but at the same time, edge length also started to vary more from site to site. Modern humans living after about 50,000 years ago produced the flakes with both the longest and the shortest sharp edges for their size. It looked as if humans had learned how to make more efficient flakes, but they didn’t always put that knowledge to work.

But that variation may actually be a sign of technological progress for early humans.

Being able to get a longer-edged flake out of a single strike is a really efficient use of stone, which gives you an advantage when you’re short on resources or when you have to carry a stone a long distance to work or use it. But there are other ways to make sharp edges—for instance, the small, sharp bladelets from the Upper Paleolithic at Abri Pataud cave shelter in France have very short edges but clearly demonstrate sophisticated, efficient craftsmanship.

This stone biface from the Abri Pataud rock shelter was first shaped by Neanderthals around 100,000 years ago, but modern humans found it and re-shaped it for their own use about 20,000 years ago. Sémhur via Wikimedia Commons

This stone biface from the Abri Pataud rock shelter was first shaped by Neanderthals around 100,000 years ago, but modern humans found it and re-shaped it for their own use about 20,000 years ago. Sémhur via Wikimedia CommonsMeanwhile, the same precision and skill that allowed production of longer edges also allowed toolmakers to vary their edge length for techniques like Levallois or for making short bladelets. Comparing the length of sharp flake edges still offers a good window into the development of the control and skill necessary to do it.

And sometimes a sharper edge wasn’t the answer. “The production and use of projectile tools was critical in some contexts, while in others, simple thick flakes may have represented a selective advantage,” Režek and his colleagues wrote.

The ability to adapt technique to context is actually pretty sophisticated, and that may be what’s behind the increase in variation among flake edges over time. Looking broadly at all these sites, it appears that human culture got better at producing sharp stone flakes over time, even as hominins apparently learned to vary the results as needed.

More questions to answer

Režek’s findings generally support what archaeologists have understood for years about the general trend toward skill and complexity in early human technology, but it’s one of the first studies comparing large numbers of artifacts across so much time and distance. Edge length gives archaeologists a standardized, concrete way to look at the big picture of human cultural evolution, which has been one of the biggest challenges for Paleolithic archaeologists so far.

If archaeologists can find ways to apply that method to other aspects of stone tool making or in other geographic areas, that could help them tackle some big-picture questions about the development of human culture and cognition.

“It would be interesting to know how these trends hold up when more data are included, for example from early Neanderthals with systematic blade production or more of the varied assemblages associated with anatomically modern humans in North Africa,” wrote Reynolds. “It would also be interesting to consider Holocene knapped lithic assemblages, including those from Australia and the Americas.”

Nature, 2017.

DOI: 10.1038/s41559-018-0488-4 (About DOIs).

https://arstechnica.com/science/2018/03/new-study-tracks-the-evolution-of-stone-tools/

![]() 6 new categories and 72 new items added to the shop!

6 new categories and 72 new items added to the shop!![]() 6 new categories and 72 new items added to the shop!

6 new categories and 72 new items added to the shop!