|

|

Poe's

Evolving

Views

on "Fashion"

Here

in full are

reproduced the two reviews for the

debut run of "Fashion" that Poe published in The Broadway Journal.

They have merit, not merely because

Poe was the only of Mowatt's critics to go on to become a world-famous

poet and author, but because the reviews themselves are

remarkable. In them, Poe goes beyond the duty of the typical

commercial drama critic. He does not stop at only answering

the

question of "Is this production sufficiently amusing to justify the

price of admission?" -In these two rather lengthy

reviews, Poe

puts himself in the position of a literary and cultural critic, asking,

"Does this play demonstrate literary merit?" and "Does it in any

way enunciate

some unique quality about being an inhabitant of the U.S. at

this time in history in a way that is distinct from European

culture?" It appears that it was primarily new ideas about

how

"Fashion"

might answer this last question that called Poe back to the play for a

second visit.

Poe

attended the play's premiere at the Park Theater on Broadway. His first

review was published in The

Broadway Journal

on March 29, 1849. Living in a time that was completely innocent of the

concept of "spoilers," he began his review with a complete rundown

of every single significant incident in the entire plot along

with colorful commentary on his opinions of the characters:

|

THE

plot of “Fashion” runs thus: Adam

Trueman, a blunt, warm-hearted, shrewd, irascible, wealthy, and

generous old

farmer of Cattaraugus County, N. Y., had a daughter, (Ruth) who eloped

with an

adventurer. The father forgave the daughter, but resolving to

disappoint the

hopes of the fortune hunter, gave the couple a bare subsistence. In

consequence

of this, the husband maltreated, and finally abandoned the wife, who

returned,

broken-hearted, to her father’s house and there died, after giving

birth to a

daughter, Gertrude That she might escape the ills

of fortune-hunting by

which her mother was destroyed, Trueman sent the child, of an early

age, to be

brought up by relatives in Geneva; giving his own neighbours to

understand that

she was dead. The Geneva friends were instructed to educate her in

habits of

self-dependence, and to withhold from her the secret of her parentage,

and

heir-ship; — the grandfather’s design being to secure for her a husband

who

will love her solely for herself. The friends by advice of the

grandfather,

procured for her when grown up to womanhood, a situation as music

teacher in

the house of Mr. Tiffany, a quondam foot-peddler, and now by dint of

industry a

dry-goods merchant doing a flashy if not flourishing business; much of

his

success having arisen from the assistance of Trueman, who knew him and

admired

his hones: industry as a travelling peddler.

The

efforts of the drygoods

merchant, however, are insufficient

to keep pace with the extravagance of his wife, who has become infected

with a

desire to shine as

a lady of fashion, in which desire she is seconded

by her daughter,

Seraphina, the musical pupil of Gertrude. The follies of the mother and

daughter so far involve Tiffany as to lead him into a forgery of a

friend’s

endorsement. This crime is suspected by his confidential clerk,

Snobson, an

intemperate blackguard, who at length extorts from his employer a

confession,

under a promise of secrecy provided that Seraphina shall become Mrs.

Snobson.

Mrs. Tiffany, however, is by no means privy to this arrangement: she is

anxious

to secure a title for Seraphina, and advocates the pretensions of Count

Jolimaitre, a quondam English cook, barber and valet, whose real name

was

Gustave Treadmill, and who, having spent much time at Paris, suddenly

took

leave of that city, for that city’s good, and his own; abandoning to

despair a

little laundress (Millinette) to whom he was betrothed, but who had

rashly

entrusted him with the whole of her hard earnings during life.

Gertrude

is beloved (for her

own sake) by Colonel Howard “of

the regular army,” and returns his affection. The Colonel, however,

makes no

proposal, because he considers that his salary of “fifteen hundred a

year” is

no property of his own, but belongs to his creditors. He has endorsed

for a

friend to the amount of seven thousand dollars, and is left to settle

the debt

as he can. He talks, therefore, of resigning, going west, making a

fortune,

returning, and then offering his hand with his fortune, to Gertrude.

At

this juncture, Trueman

pays a visit to his old friend Tiffany,

and is put at fault in respect to the true state of Gertrude’s heart

(and

indeed of everything else) by the tattle of Prudence, Mrs. Tiffany’s

old-maiden

sister. She gives the old man to understand that Gertrude

is in love with T. Tennyson Twinkle, a

poet who is in the sad habit of reading aloud his own verses, but who

has

really very respectable pretensions, as times go. T. T. T.

nevertheless, has no

thought of Gertrude, but is making desperate love to the imaginary

money-bags

of Seraphina. He is rivalled, however, not only by the Count, but by

Augustus

Fogg, a gentleman of excessive haut ton, who wears

black and has a

general indifference to everything but hot suppers.

|

|

|

Millinette,

in the meantime,

has followed her deceiver to

America, and happens to make an engagement as femme de chambre

and

general instructor in Parisian modes, at the very house (of all houses

in the

world) where her Gustave, as Count Jolimaitre, is paying his addresses

to Miss

Tiffany. The laundress recognizes the cook, who, at first overwhelmed

with

dismay, finally recovers his self-possession, and whispers to his

betrothed a

place of appointment at which he promises to “explain all.” This

appointment is

overheard by Gertrude, who for some time has had her suspicions of the

Count.

She resolves to personate Millinette in the interview, and thus obtain

means of

exposing the impostor. Contriving therefore to detain the femme

de chambre

from the assignation, she herself (Gertrude) blowing out the candles

and

disguising her voice meets the Count at the appointed room in Tiffany’s

house,

while the rest of the company (invited to a ball) are at supper. In

order to

accomplish the detention of Millinette, she has been forced to give

some

instructions to Zeke (re-baptized Adolph by Mrs. Tiffany) a negro

footman in

the Tiffany livery. These instructions are overheard by Prudence, who

mars

everything by bringing the whole household into the room of appointment

before

any secret has been extracted from the Count.

Matters are made worse for Gertrude by a futile attempt on the Count’s

part to

conceal himself in a closet. No explanations are listened to. Mrs.

Tiffany and

Seraphina are in a great rage. Howard is in despair — and True man

entertains

so bad an opinion of his grand-daughter that he has an idea of

suffering her

still to remain in ignorance of his relationship. The company disperse

in much

admired disorder, and everything is at odds and ends.

Finding

that she can get no

one to hear her explanations,

Gertrude writes an account of all to her friends at Geneva. She is

interrupted

by Trueman — shows him the letter — he comprehends all — and hurries

the lovers

into the presence of Mr. and Mrs. Tiffany, the former of whom is in

despair,

and the latter in high glee at information just received that Seraphina

has

eloped with Count Jolimaitre.

While

Trueman is here avowing his relationship,

bestowing Gertrude upon Howard, and relieving Tiffany from the fangs of

Snobson

by showing that person that he is an accessary to his employer’s

forgery,

Millinette enters, enraged at the Count’s perfidy to herself, and

exposes him

in full. Scarcely has she made an end when Seraphina appears in search

of her

jewels, which the Count, before committing himself by the overt act of

matrimony, has insisted upon her securing. As she does not return from

this

errand, however, sufficiently soon, her lover approaches on tip-toe to

see what

has become of her; is seen and caught by Millinette; and finding the

game up,

confesses everything with exceeding nonchalance. Trueman extricates

Tiffany

from his embarrassments on condition of his sending his wife and

daughter to

the country to get rid of their fashionable notions; and even carries

his

generosity so

far

as to establish the Count in a restaurant with the proviso

that

he, the Count, shall in the character and proper habiliments

of cook Treadmill, carry around his own advertisement to all the

fashionable

acquaintances who had solicited his intimacy while performing the rôle

of Count Jolintaitre. 1

|

After

doing away with any suspense a potential viewer might have experienced

when witnessing the end of "Fashion" themselves or discovering any

twists of its complex plot unaided, Poe now has sufficiently equipped

his readers to journey along with him as he dives into a discussion

that most truly interests him -- the relative originality

of this work.

Cover of the Broadway Journal,

1845

|

|

We

presume that not even the

author of a plot such as this,

would be disposed to claim for it anything on the score of originality

or

invention. Had it, indeed, been designed as a burlesque upon the arrant

conventionality of stage incidents in general, we should have regarded

it as a

palpable hit. And, indeed, while on the point of absolute

unoriginality, we may

as well include in one category both the events and the characters. The

testy

yet generous old grandfather, who talks in a domineering tone,

contradicts

everybody, slaps all mankind on the back, thumps his cane on the floor,

listens

to nothing, chastises all the fops, comes to the assistance of all the

insulted

women, and relieves all the dramatis personæ from

all imaginable

dilemmas: — the hen-pecked husband of low origin, led into difficulties

by his

vulgar and extravagant wife: — the die-away daughter aspiring to be a

Countess:

— the villain of a clerk who aims at the daughter’s hand through the

fears of

his master, some of whose business secrets he possesses: — the French

grisette

metamorphosed into the dispenser of the highest Parisian modes and

graces: —

the intermeddling old maid making bare-faced love to every unmarried

man she

meets: — the stiff and stupid man of high fashion who utters only a

single set

phrase: — the mad poet reciting his own verses: — the negro footman in

livery

impressed with a profound sense of his own consequence, and obeying

with

military promptness all orders from everybody: — the patient,

accomplished

and beautiful

governess, who proves in the end to be the heiress of the testy old

gentleman:

— the high-spirited officer, in love with the governess, and refusing

to marry

her in the first place because he is too poor, and

in the second place

because she is too rich: — and, lastly, the foreign

impostor with a

title, a drawl, an eye-glass, and a moustache, who

makes love to the

supposititious heiress of the play in strutting about the stage with

his

coat-tails thrown open after the fashion of Robert Macaire, and who, in

the

end; is exposed and disgraced through the instrumentality of some wife

or

mistress whom he has robbed and abandoned: — these things we say,

together with

such incidents as one person supplying another’s place at an

assignation, and

such équivoques as arise from a surprisal in such

cases — the

concealment and discovery of one of the parties in a closet, — and the

obstinate refusal of all the world to listen to an explanation, are the

common

and well-understood property of the playwright, and have been so,

unluckily

time out of mind.

But for this very reason

they should be abandoned at once.

Their hackneyism is no longer to be endured. The day has at length

arrived when

men demand rationalities in place of conventionalities. It will no

longer do to

copy, even with absolute accuracy, the whole tone of even so ingenious

and

really spirited a thing as the “School for Scandal.” It was

comparatively good

in its day, but it would be positively bad at the present day, and

imitations

of it are inadmissible at any day.

Bearing

in mind the spirit

of these observations, we may say

that “Fashion” is theatrical but not dramatic. It is a pretty

well-arranged

selection from the usual

routine of stage characters, and stage

manœuvres — but there is not one

particle of any nature beyond greenroom nature, about it. No such

events ever

happened in fact, or ever could happen; as happen in “Fashion.” Nor are

we

quarrelling, now, with the mere exaggeration of

character or incident; —

were this all, the play, although bad as comedy might be good as farce,

of

which the exaggeration of possible incongruities is the chief element.

Our

fault-finding is on the score of deficiency in verisimilitude — in

natural art

— that is to say, in art based in the natural laws of man’s heart and

understanding.2

|

|

At

this point in his critique, Poe switches from commenting

specifically on "Fashion" to using the play as an exemplar

of all the

faults of the mannered , presentation style of dramas of his day:

When

for example, Mr. Augustus Fog; (whose name by the bye has

little application to his character) says, in reply to Mrs. Tiffany’s

invitation to the conservatory, that he is “indifferent to flowers,”

and

replies in similar terms to every observation addressed to him, neither

are we

affected by any sentiment of the farcical, nor can we feel any sympathy

in the

answer on the ground of its being such as any human being would

naturally make

at all times to all queries — making no other answer to any. Were the

thing

absurd in itself we should laugh, and a legitimate effect would be

produced;

but unhappily the only absurdity we perceive is the absurdity of the

author in

keeping so pointless a phrase in any character’s mouth. The shameless

importunities of Prudence to Trueman are in the same category — that of

a total

deficiency in verisimilitude, without any compensating incongruousness

— that

is to say, farcicalness, or humor. Also in the same category we must

include the

rectangular crossings and recrossings of the dramatis personæ

on the

stage; the coming forward to the foot-lights when anything of interest

is to be

told; the reading of private

letters in a loud rhetorical tone; the preposterous soliloquising; and

the even

more preposterous “asides.” Will our play-wrights never learn, through

the

dictates of common sense, that an audience under no circumstances can

or will

be brought to conceive that what is sonorous in their own ears at a

distance of

fifty feet from the speaker cannot be heard by an actor at the distance

of one

or two?

It

must be understood that we are not condemning Mrs. Mowatt’s

comedy in particular, but the modern drama in general. Comparatively,

there is

much merit in “Fashion,” and in many respects (and those of a telling

character) it is superior to any American play. It has, in especial,

the very

high merit of simplicity in plot. What the Spanish play-wrights mean by

dramas

of intrigue are the worst acting dramas in the

world:

— the intellect of an audience call

never safely be fatigued by complexity. The

necessity for verbose explanation

on the part of Trueman at the close of “Fashion” is, however, a serious

defect.

The dénouement should in all cases be full of action

and nothing

else. Whatever cannot be explained by such action should be

communicated at the

opening of the play.3

As

a

modern viewer, accustomed to having our choice of a variety of dramatic

styles -- including a more naturalistic style of dramatic presentation

when we wish it, it is hard to not have sympathy for a

theatre critic

forced to live on a diet of constant melodrama. It is easy to have a

little empathy for the somewhat bitter tone of Poe disparaging for what

he felt was the poor

taste of the general theatre-going masses as he surmises:

The

colloquy in Mrs. Mowatt’s comedy is spirited, generally

terse, and well-seasoned at points with sarcasm of much power. The management

throughout shows the fair authoress to be thoroughly conversant with

our

ordinary stage effects, and we might say a good deal in commendation of

some of

the “sentiments” interspersed: — we are really ashamed, nevertheless,

to record

our deliberate opinion that if “Fashion” succeed at all (and we think

upon the

whole that it will) it will owe the greater portion of its success to

the very

carpets, the very ottomans, the very chandeliers, and the very

conservatories

that gained so decided a popularity for that most inane and utterly

despicable

of all modern comedies — the “London Assurance” of Boucicault.4

However

this is not the end of the review. Elements of the play that seemed to

have been added in rehearsal went a long way to change Poe's over all

opinion of the production and persuaded him to end on a much more

hopeful note:

The

above remarks were written before the comedy’s

representation at the Park, and were based on the author’s original

MS., in

which some modifications have been made — and not at all times, we

really

think, for the better. A good point, for example, has been omitted, at

the dénouement.

In the original, Trueman (as will be seen in our digest) pardons the

Count, and

even establishes him in a restaurant, on condition

of his carrying

around to all his fashionable acquaintances his own advertisement as restaurateur.

There is a piquant, and dashing deviation, here,

from the ordinary routine

of stage “poetic justice,” which could not

have failed to tell, and which was, perhaps, the one original point of

the

play. We can conceive no good reason for its omission. A scene, also,

has been

introduced, to very little purpose. We watched its effect narrowly and

found it

null. It narrated nothing; it illustrated nothing; and was absolutely

nothing

in itself. Nevertheless it might have been

introduced for the purpose of

giving time for some other scenic arrangements going on out of sight.5

Poe

then jaunts

through the last two paragraphs of this review, covering material that

another drama critic might have used to make up their entire entry on

the play. He rushes through these thoughts at such a blunt

and

break-neck pace that they seem to be mere transcriptions of impressions

he jotted down during the performance. Poe even

unapologetically

includes specific line readings for actors and suggestions for

improvements on bits of blocking:

A

well-written prologue was well-delivered by Mr. Crisp, whose

action is far better than his reading – although the latter, with one

exception, is good. It is pure irrationality to recite verse, as if it

were

prose, without distinguishing the lines: -- we shall touch this subject

again.

As the Count, Mr. Crisp did everything that could be done: -- his grace

of

gesture is preeminent. Miss Horne looked charmingly as Seraphina.

Trueman and

Tiffany were represented with all possible effect by Chippendale and

Barry: --

and Mrs. Barry as Mrs. Tiffany was the life of the play. Zeke was

caricatured.

Dyott makes a bad colonel – his figure is too diminutive. Prudence was

well

exaggerated by Mrs. Knight – and the character in her hands, elicited

more applause

than anyone other of the dramatis

personae.

Some of

the author’s

intended points were lost through the inevitable inadvertences of a

first

representation – but upon the whole, everything went off exceedingly

well. To

Mrs. Barry we would suggest that the author’s intention was, perhaps,

to have elite pronounced ee-light, and bouquet,

bokett: -- the effect

would be more

certain. To Zeke, we would say, bring up the table bodily by all means

(as

originally designed) when the fow tool

is called for. The scenery was very good indeed – and the carpet,

ottomans,

chandelier, etc. were also excellent of their kind. The entire “getting

up” was

admirable. “Fashion,” upon the whole, was well received by a large,

fashionable, and critical audience; and will succeed to the extent we

have

suggested above. Compared with the generality of modern dramas, it is a

good

play – compared with most American dramas it is a very

good one – estimated by the natural principles of dramatic

art, it is altogether unworthy of notice.6

|

Poe returned to

"Fashion" for the next week's issue of The Broadway Journal.

Despite the many flaws he found in the writing and execution of

Mowatt's drama, something in the production had captured his

attention. He immediately confesses to have attended a

performance of the play every night of the intervening week. "Fashion"

had gone from being a cheap "School for Scandal" knockoff to being a

bit of an obsession for him. His tone is no longer brusque

and

dismissive, but is immediately apologetic: Poe returned to

"Fashion" for the next week's issue of The Broadway Journal.

Despite the many flaws he found in the writing and execution of

Mowatt's drama, something in the production had captured his

attention. He immediately confesses to have attended a

performance of the play every night of the intervening week. "Fashion"

had gone from being a cheap "School for Scandal" knockoff to being a

bit of an obsession for him. His tone is no longer brusque

and

dismissive, but is immediately apologetic:

SO

deeply have we felt interested

in

the question of Fashion’s success or failure, that we have been to see

it every

night since its first production; making careful note of its merits and

defects

as they were more and more distinctly developed in the gradually

perfected

representation of the play.

We

are enabled, however, to say but little either in

contradiction or in amplification of our last week’s remarks — which

were based

it will be remembered, upon the original MS. of the fair authoress, and

upon

the slightly modified performance of the first night. In what we then

said we

made all reasonable allowances for inadvertences at the outset — lapses

of

memory in the actors — embarrassments in scene-shifting — in a word for

general

hesitation and want of finish. The comedy now,

however, must be

understood as having all its capabilities fairly brought out, and the

result of

the perfect work is before us.7

As pointed

out earlier, Poe, in

many ways, is almost comically disinterested in performing the normal

function expected of a newspaper drama critic of the time. He does not

seem to care a whit about telling a theatre patron if they're getting

good value for their ticket price. Instead, he seems to

presciently be addressing us, readers from the future, trying to answer

the question "Is there any valid reason why this play should wind up in

theatre history books?" After repeated viewings,

Poe decides to change

his answer to yes. It is a grudging and conditional yes, but

it

is a yes:

In

one respect, perhaps, we have done Mrs. Mowatt unintentional

injustice. We are not quite sure, upon reflection, that her entire

thesis is

not an original one. We can call to mind no drama, just now, in which

the

design can be properly stated as the satirizing of fashion as

fashion.

Fashionable follies, indeed, as a class of folly in general, have been

frequently made the subject of dramatic ridicule — but the distinction

is

obvious — although certainly too nice a one to be of any practical

avail save

to the authoress of the new

comedy. Abstractly we may admit some pretension to originality of plan

— but,

in the presentation, this shadow of originality vanishes.

We

cannot, if we would, separate the dramatis personæ

from the moral they illustrate; and the characters overpower the moral.

We see

before us only personages with whom we have been familiar time out of

mind: —

when we look at Mrs. Tiffany, for example, and hear her speak, we think

of Mrs.

Malaprop in spite of ourselves, and in vain endeavour to think of

anything

else. The whole conduct and language of the comedy, too, have about

them the unmistakable flavor of the green-room. We doubt if a single point

either in the one or the other, is not a household thing with every

play-goer.

Not a joke is any less old than the hills — but this conventionality is

more

markedly noticeable in the sentiments, so-called. When, for instance,

Gertrude

in quitting the stage, is made to say “if she fail in a certain scheme

she will

be the first woman who was ever at a loss for a stratagem,” we are

affected

with a really painful sense of the antique. Such things are only to be

ranked

with the stage “properties,” and are inexpressibly wearisome and

distasteful to

everyone who hears them. And that they are sure to elicit what appears

to be

applause, demonstrates exactly nothing at all. People at these points

put their

hands together, and strike their canes against the floor for the reason

that

they feel these actions to be required of them as a matter of course,

and that

it would be ill-breeding not to comply with the requisition. All the

talk put

into the mouth of Mr. Trueman, too, about “when honesty shall be found

among

lawyers, patriotism among statesmen,” etc. etc. must be included in the

same

category.

The

error of the dramatist lies in not estimating at its true value the

absolutely

certain “approbation” of the audience in such cases

— an approbation

which is as pure a conventionality as are the “sentiments” themselves.

In

general it may be boldly asserted that the clapping of hands and the

rattling

of canes are no tokens of the success of any play —

such success as the

dramatist should desire: — let him watch the countenances

of his

audience, and remodel his points by these. Better still — let him “look

into

his own heart and write” — again better still (if he have the capacity)

let him

work out his purposes à priori from the infallible

principles of a

Natural Art.

We

are delighted to find, in the reception of Mrs. Mowatt’s

comedy, the clearest indications of a revival of the American drama —

that is

to say of an earnest disposition to see it revived. That the drama, in

general,

can go down, is the most untenable of all untenable ideas. Dramatic art

is, or

should be, a concentralization of all that which is entitled to the

appellation

of Art. When sculpture shall fail, and painting shall fail, and poetry,

and

music; — when men shall no longer take pleasure in eloquence, and in

grace of

motion, and in the beauty of woman, and in truthful representations of

character, and in the consciousness of sympathy in their enjoyment of

each and

all, then and not till then, may we look for that

to sink into

insignificance, which, and which alone, affords opportunity for the

conglomeration of these infinite and imperishable sources of delight.8

Although

flawed, Poe found "Fashion" to have merit. However he does

have

some problem in getting to the specifics of exactly where those merits

lie. Perhaps Poe found himself enthralled by that rarest and hardest to

explain of theatrical phenomena - the Broadway hit. As with "Fashion,"

the text or individual theatrical elements of one of these singular

productions may on the

surface

be formulaic, derivative,

or even in retrospect appear trite. However,

because of certain confluences of culture and art, such memorable,

once-in-a-generation shows manage to capture an essence of what it

means to exist in a certain time and place that fascinates audiences

and uniquely excites their imaginations. "Fashion" might have been the

"Camelot," "My Fair Lady," "Rent," "Les Mis," or "Hamilton" of its day.

Poe found himself enthralled by that rarest and hardest to

explain of theatrical phenomena - the Broadway hit. As with "Fashion,"

the text or individual theatrical elements of one of these singular

productions may on the

surface

be formulaic, derivative,

or even in retrospect appear trite. However,

because of certain confluences of culture and art, such memorable,

once-in-a-generation shows manage to capture an essence of what it

means to exist in a certain time and place that fascinates audiences

and uniquely excites their imaginations. "Fashion" might have been the

"Camelot," "My Fair Lady," "Rent," "Les Mis," or "Hamilton" of its day.

Buoyed

by the

enthusiasm witnessing such a phenomenon can engender, Poe continued his

review with his fondest hopes for the future for the theatre in the

U.S.:

There

is not the least danger, then, that the drama shall fail.

By the spirit of imitation evolved from its own nature, and to a

certain extent

an inevitable consequence of it, it has been kept absolutely

stationary

for a hundred years,

while its sister arts have rapidly flitted by and left it out of sight.

Each

progressive step of every other art seems to drive

back the drama to the

exact extent of that step — just as, physically, the objects by the

way-side

seem to be receding from the traveller in a coach. And the practical

effect, in

both cases is equivalent: — but yet, in fact, the drama has not

receded: on the

contrary it has very slightly advanced in one or two of the plays of

Sir Edward

Lytton Bulwer. The apparent recession or degradation, however, will, in

the

end, work out its own glorious recompense. The extent — the excess of

the

seeming declension will put the right intellects upon the serious

analysis of

its causes. The first noticeable result of this analysis will be a

sudden

indisposition on the part of all thinking men to commit themselves any

farther

in the attempt to keep up the present mad — mad because false —

enthusiasm

about “Shakspeare and the musical glasses.” Quite willing, of course,

to give

this indisputably great man the fullest credit for what he has done —

we shall

begin to ask our own understandings why it is that there is so very —

very much

which he has utterly failed to accomplish.

When

we arrive at this epoch, we are safe. The next step may be

the electrification of all mankind by the representation of a

play that

may be neither tragedy, comedy, farce, opera, pantomime, melodrama, or

spectacle, as we now comprehend these terms, but which may retain some

portion

of the idiosyncratic excellences of each, while it introduces a new

class of

excellence as yet unnamed because as yet undreamed-of in the world. As

an

absolutely necessary condition of its existence this play may usher in

a

thorough remodification of the theatrical physique.

This

step being fairly taken, the drama will be at once side by

side with the more definitive and less comprehensive arts which have

outstripped it by a century: — and now not merely will it outstrip them

in

turn, but devour them altogether. The drama will be all in all.9

Again

as in his last entry in the Broadway

Journal, Poe populates his last two paragraphs with the

sort of material other drama critics would have stretched into an

entire review:

We

cannot conclude these random

observations without again

recurring to the effective manner in which “Fashion” has been brought

forward

at the Park. Whatever the management and an excellent company could do

for the

comedy has been done. Many obvious improvements have been adopted since

the

first representation, and a very becoming deference has been

manifested, on the

part of the fair authoress and of Mr. Simpson, to everything wearing

the aspect

of public opinion — in especial to every reasonable hint from the

press. We are

proud, indeed, to find that many even of our own ill-considered

suggestions,

have received an attention which was scarcely their due.

In “Fashion” nearly all the Park

company have won new laurels.

Mr. Chippendale did wonders. Mr. Crisp was, perhaps, a little too

gentlemanly

in the Count — he has subdued the part, we think, a

trifle too much: —

there is a true grace of manner of which he finds

it difficult to divest

himself, and which occasionally interferes with his conceptions. Miss

Ellis did

for Gertrude all that any mortal had a right to expect. Millinette

could

scarcely have been better represented. Mrs. Knight as Prudence is

exceedingly

comic. Mr. and Mrs. Barry do invariably well — and of Mr. Fisher we

forgot say

in our last paper that he was one of the strongest points of the play.

As for

Miss Horne — it is but rank heresy to imagine

that there could be any difference of opinion respecting her.

She sets

at naught all criticism in winning all hearts. There is about her

lovely

countenance a radiant earnestness of expression

which is sure to play a

Circean trick with the judgment of every person who beholds it.10

Although he does not become blind to "Fashion's" faults, this second

review indicates that Poe has been beguiled by the show's charms. If

nothing else, these two reviews give us a picture of this sometimes

blunt and cynical critic falling in love with a play in spite of

himself.

NOTES

1. Edgar

Allan

Poe. "The New Comedy by Mrs. Mowatt." Broadway

Journal. March 29, 1845, p. 112-116.

2.

ibid. p. 117-118.

3.

ibid. p. 118-120.

4.

ibid. p. 120.

5.

ibid. p. 121.

6. ibid.

7.

Edgar Allan

Poe. "Prospects of the Drama -- Mrs. Mowatt’s Comedy." Broadway

Journal. April 5,

1845, p. 124

8.

ibid. p. 125-128.

9.

ibid p. 128-129.

10. ibid p. 129.

Back To: Poe and Mowatt Homepage

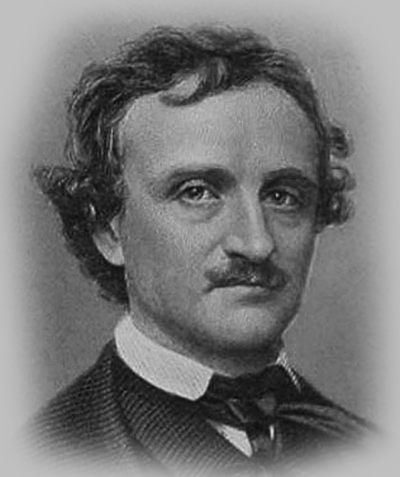

Edgar

Allan

Poe’s

Favorite

Poe's

Portrait

of Mowatt

Was Poe T. T. Twinkle?

Back

to Lady Actress Index Page

Back

to Lady Actress Index Page

|

Poe returned to

"Fashion" for the next week's issue of The Broadway Journal.

Despite the many flaws he found in the writing and execution of

Mowatt's drama, something in the production had captured his

attention. He immediately confesses to have attended a

performance of the play every night of the intervening week. "Fashion"

had gone from being a cheap "School for Scandal" knockoff to being a

bit of an obsession for him. His tone is no longer brusque

and

dismissive, but is immediately apologetic:

Poe returned to

"Fashion" for the next week's issue of The Broadway Journal.

Despite the many flaws he found in the writing and execution of

Mowatt's drama, something in the production had captured his

attention. He immediately confesses to have attended a

performance of the play every night of the intervening week. "Fashion"

had gone from being a cheap "School for Scandal" knockoff to being a

bit of an obsession for him. His tone is no longer brusque

and

dismissive, but is immediately apologetic: