| |

|

|

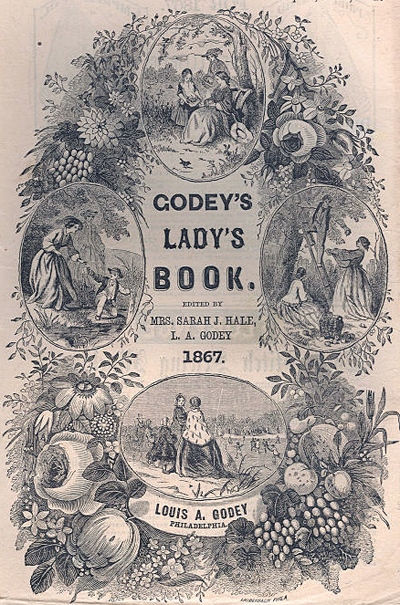

Poe's Portrait of Mowatt for Godey's Lady's Book

A year after writing about her in The Broadway Journal,

Poe edited his reviews of his various views of Mowatt's play "Fashion"

and her various performances into a portrait of her to be included with

his impressions of other outstanding members of New York's literati

that he completed for Godey's Lady Book.

Because it is perhaps one of the most comprehensive evaluations we have of her

work as a creative artist, I wish to reproduce here in full:

|

ANNA CORA MOWATT.

MRS. MOWATT is in some respects a

remarkable woman, and has undoubtedly wrought a deeper impression upon the

public than any one of her sex in America.

She became first known through her

recitations. To these she drew large and discriminating audiences in Boston,

New York, and elsewhere to the north and east. Her subjects were much in the

usual way of these exhibitions, including comic as well as serious pieces,

chiefly in verse. In her selections she evinced no very refined taste,

but was probably influenced by the elocutionary rather than by the literary

value of her programmes. She read well; her voice was melodious; her

youth and general appearance excited interest, but, upon the whole, she

produced no great effect, and the enterprise may be termed unsuccessful,

although the press, as is its wont, spoke in the most sonorous tones of her

success.

It was during these recitations that

her name, prefixed to occasional tales, sketches and brief poems in the

magazines, first attracted an attention that, but for the recitations, it might

not have attracted.

Her sketches and tales may be said

to be cleverly written. They are lively, easy, conventional,

scintillating with a species of sarcastic wit, which might be termed good were

it in any respect original. In point of style — that is to say, of mere English,

they are very respectable. One of the best of her prose papers is entitled

“Ennui and its Antidote,” published in “The Columbian Magazine” for June, 1845.

The subject, however, is an exceedingly hackneyed one. |

|

|

In looking carefully over her poems,

I find no one entitled to commendation as a whole; in very few of them do I

observe even noticeable passages, and I confess that I am surprised and

disappointed at this result of my inquiry; nor can I make up my mind that there

is not much latent poetical power in Mrs. Mowatt. From some lines addressed to

Isabel M——, I copy the opening stanza as the most favorable specimen which I

have seen of her verse.

Forever vanished from thy cheek

Is life’s unfolding rose —

Forever quenched the flashing smile

That conscious beauty knows!

Thine orbs are lustrous with a light

Which ne’er illumes the eye

Till heaven is bursting on the sight

And earth is fleeting by.”

|

|

In this there is much force, and the

idea in the concluding quatrain is so well put as to have the air of

originality. Indeed, I am not sure that the thought of the last two lines is

not original; — at all events it is exceedingly natural and impressive.

I say “natural,” because, in any imagined ascent from the orb we

inhabit, when heaven should “burst on the sight” — in other words, when the

attraction of the planet should be superseded by that of another sphere, then

instantly would the “earth” have the appearance of “fleeting by.” The

versification, also, is much better here than is usual with the poetess. In

general she is rough, through excess of harsh consonants. The whole poem is of

higher merit than any which I can find with her name attached; but there is

little of the spirit of poesy in anything she writes. She evinces more feeling

than ideality.

Her first decided success was with

her comedy, “Fashion,” although much of this success itself is referable to the

interest felt in her as a beautiful woman and an authoress.

The play is not without merit. It

may be commended especially for its simplicity of plot. What the Spanish

playwrights mean by dramas of intrigue, are the worst acting dramas in

the world; the intellect of an audience can never safely be fatigued by

complexity. The necessity for verbose explanation, however, on the part of

Trueman, at the close of the play, is in this regard a serious defect. A dénouement

should in all cases be taken up with action — with nothing else. Whatever

cannot be explained by such action should be communicated at the opening of the

story.

In the plot, however estimable for

simplicity, there is of course not a particle of originality of

invention. Had it, indeed, been designed as a burlesque upon the arrant

conventionality of stage incidents in general, it might have been received as a

palpable hit. There is not an event, a character, a jest, which is not a

well-understood thing, a matter of course, a stage-property time out of mind.

The general tone is adopted from “The School for Scandal,” to which, indeed,

the whole composition bears just such an affinity as the shell of a locust to

the locust that tenants it — as the spectrum of a Congreve rocket to the

Congreve rocket itself. In the management of her imitation,

nevertheless, Mrs. Mowatt has, I think, evinced a sense of theatrical effect or

point which may lead her, at no very distant day, to compose an exceedingly taking,

although it can never much aid her in composing a very meritorious drama.

“Fashion,” in a word, owes what it had of success to its being the work of a

lovely woman who had already excited interest, and to the very commonplaceness

or spirit of conventionality which rendered it readily comprehensible and

appreciable by the public proper. It was much indebted, too, to the carpets,

the ottomans, the chandeliers and the conservatories, which gained so decided a

popularity for that despicable mass of inanity, the “London Assurance” of

Bourcicault.

Since “Fashion,” Mrs. Mowatt has

published one or two brief novels in pamphlet form, but they have no particular

merit, although they afford glimpses (I cannot help thinking) of a genius as

yet unrevealed, except in her capacity of actress.

|

|

In this capacity, if she be but true

to herself, she will assuredly win a very enviable distinction. She has done

well, wonderfully well, both in tragedy and comedy; but if she knew her own

strength she would confine herself nearly altogether to the depicting (in

letters not less than on the stage) the more gentle sentiments and the most

profound passions. Her sympathy with the latter is evidently intense. In the

utterance of the truly generous, of the really noble, of the unaffectedly

passionate, we see her bosom heave, her cheek grow pale, her limbs tremble, her

lip quiver, and nature’s own tear rush impetuously to the eye. It is this

freshness of the heart which will provide for her the greenest laurels. It is

this enthusiasm, this well of deep feeling,

which should be made to prove for her an inexhaustible source of fame. As an

actress, it is to her a mine of wealth worth all the dawdling instruction

in the world. Mrs. Mowatt, on her first appearance as Pauline, was quite as

able to give lessons in stage routine to any actor or actress in

America, as was any actor or actress to give lessons to her. Now, at

least, she should throw all “support” to the winds, trust proudly to her own

sense of art, her own rich and natural elocution, her beauty, which is unusual,

her grace, which is queenly, and be assured that these qualities, as she now

possesses them, are all sufficient to render her a great actress, when

considered simply as the means by which the end of natural acting is to be

attained, as the mere instruments by which she may effectively and unimpededly

lay bare to the audience the movements of her own passionate heart.

Indeed, the great charm of her

manner is its naturalness. She looks, speaks and moves, with a well-controlled

impulsiveness, as different as can be conceived from the customary rant and

cant, the hack conventionality of the stage. Her voice is rich and voluminous,

and although by no means powerful, is so well managed as to seem so. Her

utterance is singularly distinct, its sole blemish being an occasional

Anglicism of accent, adopted probably from her instructor, Mr. Crisp. Her

reading could scarcely be improved. Her action is distinguished by an ease and

self-possession which would do credit to a veteran. Her step is the perfection

of grace. Often have I watched her for hours with the closest scrutiny, yet

never for an instant did I observe her in an attitude of the least awkwardness

or even constraint, while many of her seemingly impulsive gestures spoke in

loud terms of the woman of genius, of the poet imbued with the profoundest

sentiment of the beautiful in motion.

Her figure is slight, even fragile.

Her face is a remarkably fine one, and of that precise character best adapted

to the stage. The forehead is, perhaps, the least prepossessing feature,

although it is by no means an unintellectual one. Hair light auburn, in rich

profusion, and always arranged with exquisite taste. The eyes are gray,

brilliant and expressive, without being full. The nose is well formed, with the

Roman curve, and indicative of energy. This quality is also shown in the

somewhat excessive. prominence of the chin.

The mouth is large, with brilliant and even teeth and flexible lips, capable of

the most instantaneous and effective variations of expression. A more radiantly

beautiful smile it is quite impossible to conceive.1

|

In this summary, Poe was even more

parsimonious with his praise than he tended to be in the individual

reviews that went together in its making. I think it is important for the reader to remember, though, that Poe is ranking

Mowatt alongside established literary figures of her day in this

collection of essays. She was at that time a twenty-seven-year old

newcomer with only her plays "Fashion," "Armand," and handful of poems

to show. From the text, I think it is clear that he feels it is most

appropriate to comment on her potential at this early point in her

career.

important for the reader to remember, though, that Poe is ranking

Mowatt alongside established literary figures of her day in this

collection of essays. She was at that time a twenty-seven-year old

newcomer with only her plays "Fashion," "Armand," and handful of poems

to show. From the text, I think it is clear that he feels it is most

appropriate to comment on her potential at this early point in her

career.

He makes conspicuous mention of the fact

that she was both young and a woman. In the 1840's both of these

factors would make her a remarkable specimen in literary circles --

although Poe does include eleven women among his literati. He turns on

them the same unsparing critical gaze he does the men.

Poe got into a certain amount of trouble over these biographical

sketches. An editor's note appearing in the issue in which the essay on

Anna Cora Mowatt appears reads:

“THE AUTHORS AND MR. POE.

— We have received several letters from New York, anonymous and from

personal friends,

requesting us to be careful what we allow Mr. Poe to

say of the New York authors, many of whom are our personal friends. We

reply

to one and all, that we have nothing to do but

publish Mr. Poe’s opinions, not our own. Whether we agree with

Mr.

Poe’s or not is another matter. We are not to be

intimidated by a threat of the loss of a friends, or turned from our

purpose by honeyed words. Our course is onward. The

May edition was exhausted before the first of May, and we have had

orders for

hundreds from Boston and New York which we could not

supply. The first number of the series, (with autographs,) is

republished in

this number, which also contains No. 2. The usual

quantity of reading matter is given in addition to the notices.

Another note written after her sketch appeared read:

Editors’ Book Table: “We hear of some complaints having been made by

those writers who have already been noticed by

Mr. Poe. Some of the ladies have suggested that the

publisher has something to do with them. This we positively deny, and we

as

positively assert that they are published as written

by Mr. Poe, without any alteration or suggestion from us” 2

Feedback

such as the above should remind the reader that there was not universal

agreement among contemporaries who knew the parties in question with

all assertions put forth in these essays. We should keep in mind,

therefore, that just because Poe might have thought Mrs. Mowatt's plays

were being produced primarily because she was a beautiful young woman,

this was mere conjecture on his part, even though it may have been --

as the subtitle for these essays read in boldface type -- it was his

HONEST OPINION AT RANDOM RESPECTING AUTHORIAL MERITS, WITH OCCASIONAL

WORDS OF PERSONALITY.

NOTES

1. Poe. “The Literati of New York City” - No. IV) — August 1846 — Godey’s

Lady’s Book

2.Godey’s Lady’s Book, p. 144, column 1.

|

important for the reader to remember, though, that Poe is ranking

Mowatt alongside established literary figures of her day in this

collection of essays. She was at that time a twenty-seven-year old

newcomer with only her plays "Fashion," "Armand," and handful of poems

to show. From the text, I think it is clear that he feels it is most

appropriate to comment on her potential at this early point in her

career.

important for the reader to remember, though, that Poe is ranking

Mowatt alongside established literary figures of her day in this

collection of essays. She was at that time a twenty-seven-year old

newcomer with only her plays "Fashion," "Armand," and handful of poems

to show. From the text, I think it is clear that he feels it is most

appropriate to comment on her potential at this early point in her

career.